The GitHub Threat No One Saw Coming

It's 2 AM. Your security team just got the alert. Another GitHub repository claiming to have the latest exploit code for a zero-day vulnerability you read about last week. You download it. Extract it. Run it. Then everything goes silent.

That's how Web RAT gets in.

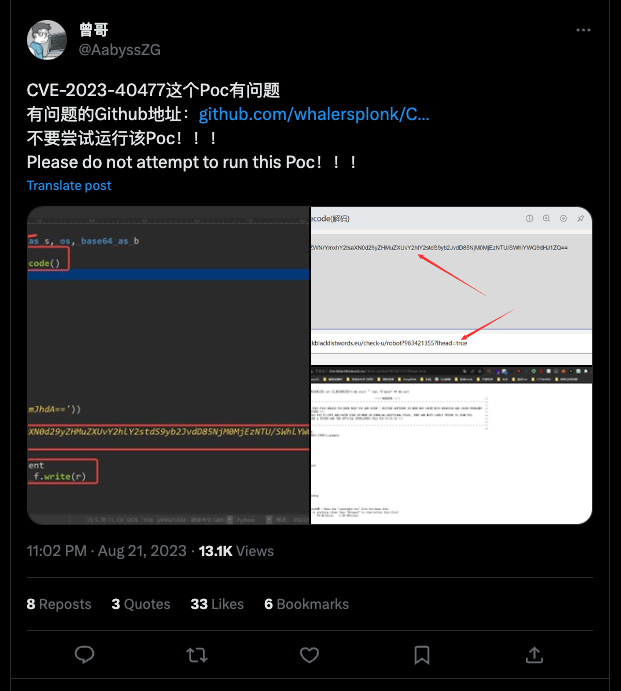

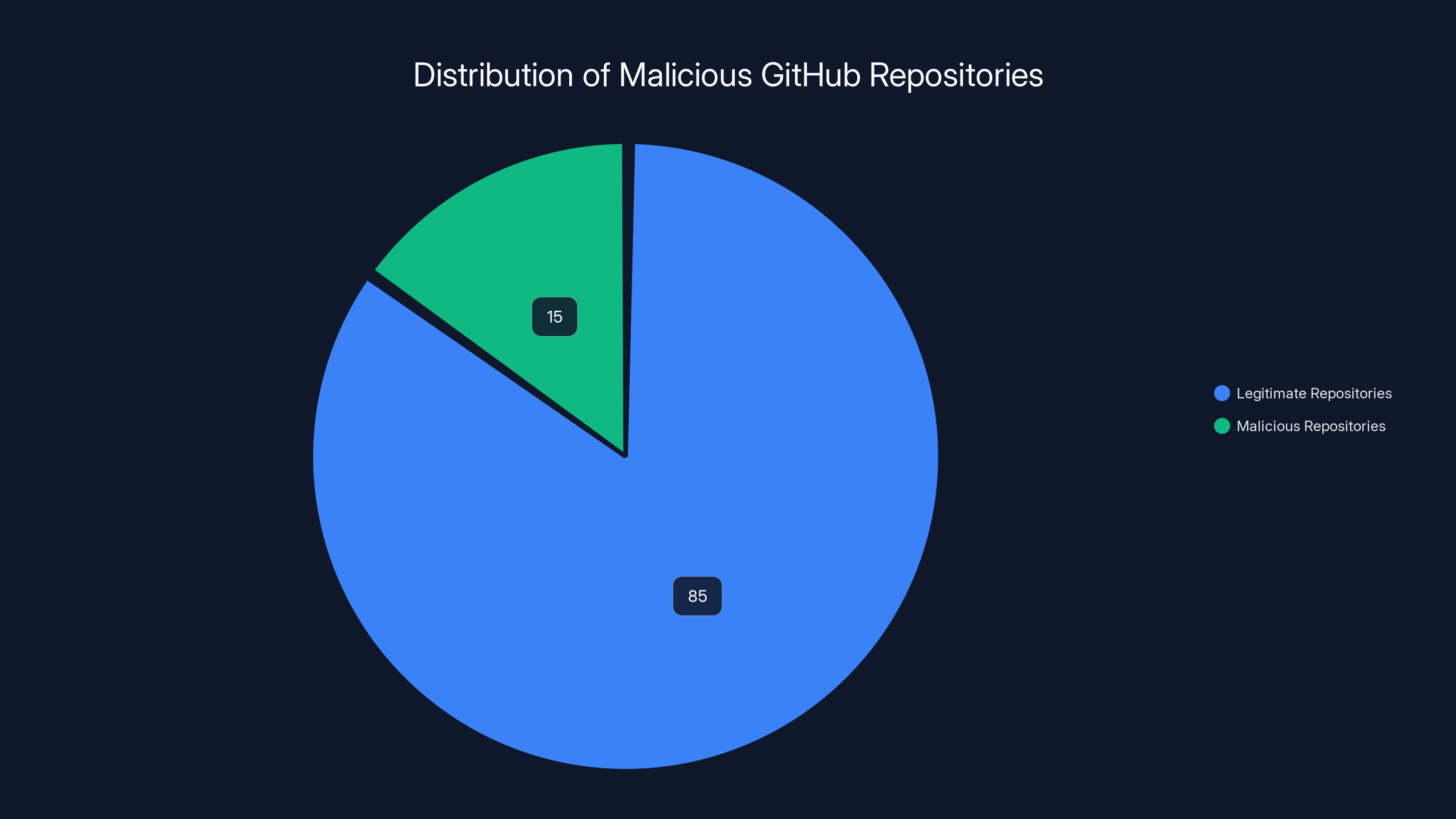

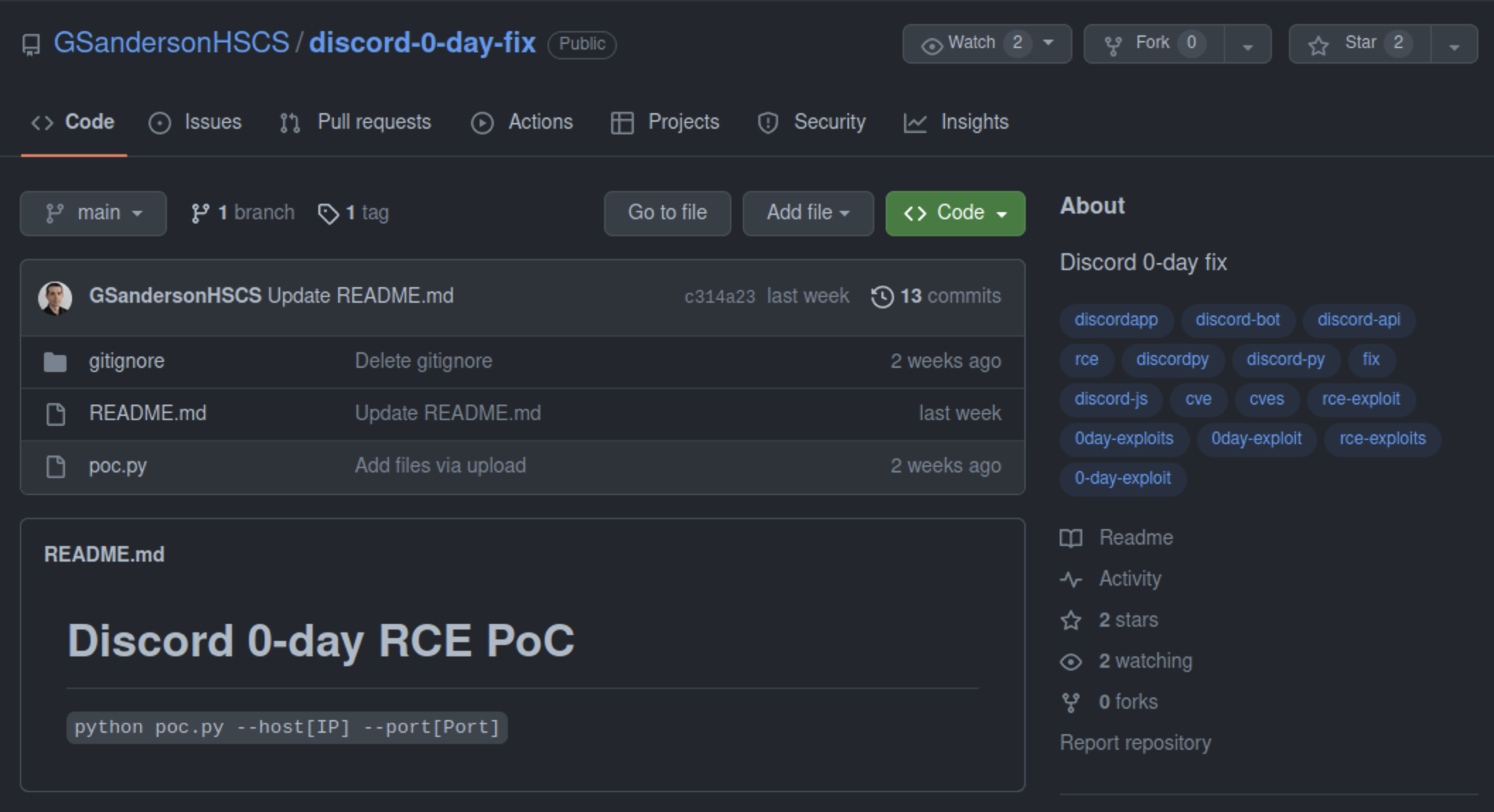

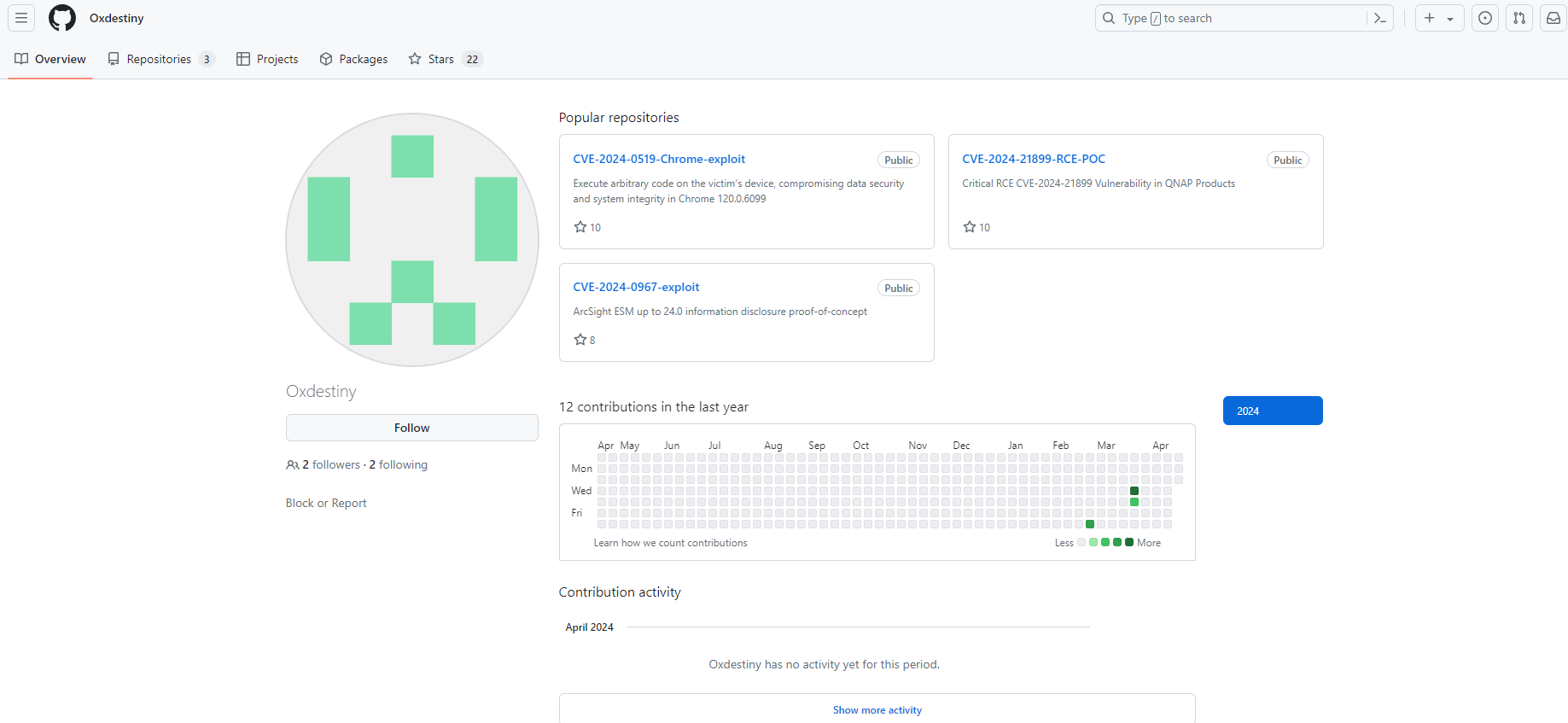

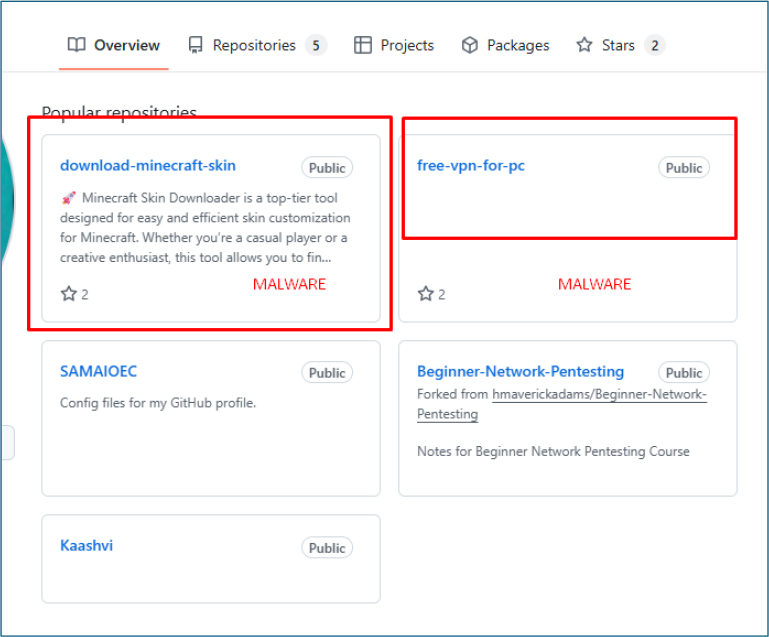

Security researchers at Kaspersky recently uncovered something that's quietly reshaping how threat actors target developers and security researchers. They found 15 malicious GitHub repositories that looked legitimate, acted legitimate, but were anything but. These repos pretended to offer proof-of-concept (PoC) exploits for real vulnerabilities. Some were even crafted using generative AI to make them sound more convincing.

Here's the thing that makes this different: GitHub isn't typically where you find sophisticated malware distribution. Yet threat actors have figured out that the platform's trust factor, combined with the security community's constant hunt for the latest exploits, creates a perfect storm. Developers and security researchers are conditioned to trust GitHub. They use it daily. They know the platform has safeguards. So when they see what appears to be a legitimate repository with proper documentation and reasonable-looking code, they let their guard down.

The Web RAT campaign that started in September 2025 represents a shift in how cybercriminals think about distribution. Instead of mass phishing campaigns or compromised websites, they're exploiting the platforms where security professionals themselves spend their time. It's predatory targeting of the hunters.

What makes this campaign particularly insidious is the AI component. Kaspersky found evidence that these fake exploits were enhanced using generative AI tools. The documentation reads naturally. The code structure looks reasonable at first glance. An automated script might flag it as suspicious, but a human reviewer scanning through legitimate GitHub repositories might miss it entirely. The researchers weren't using AI just to generate malware code—they were using it to make malware distribution more convincing.

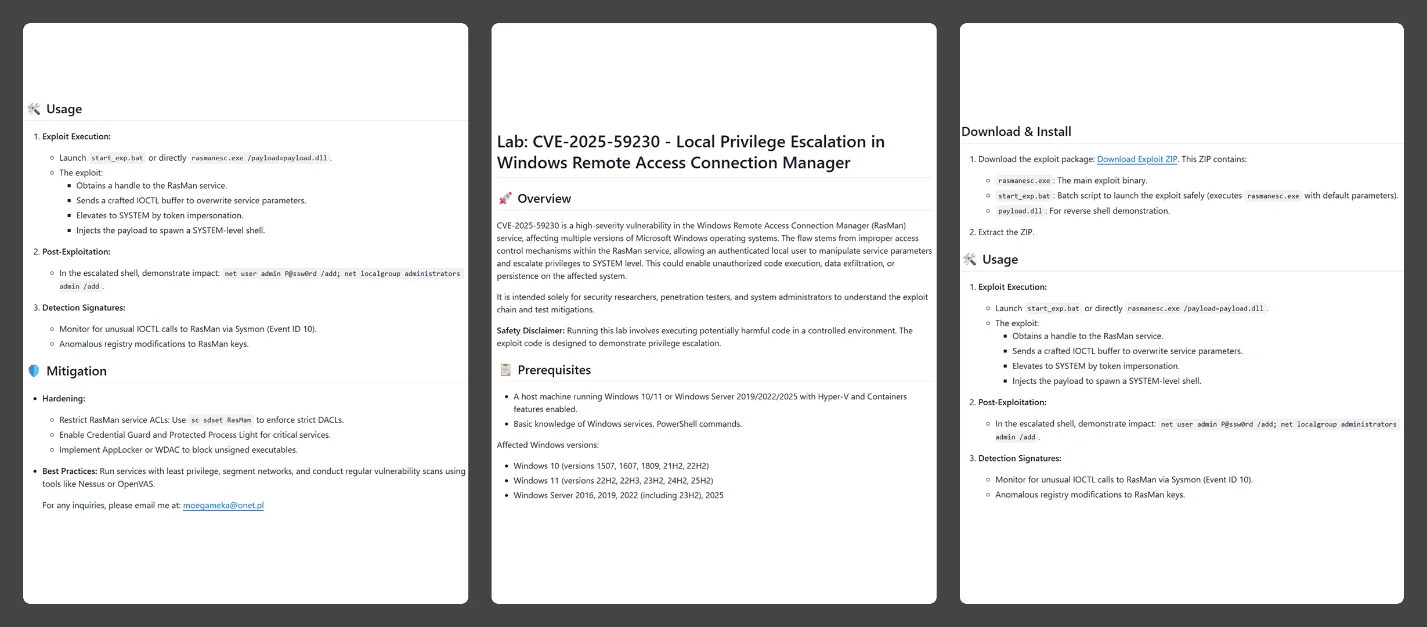

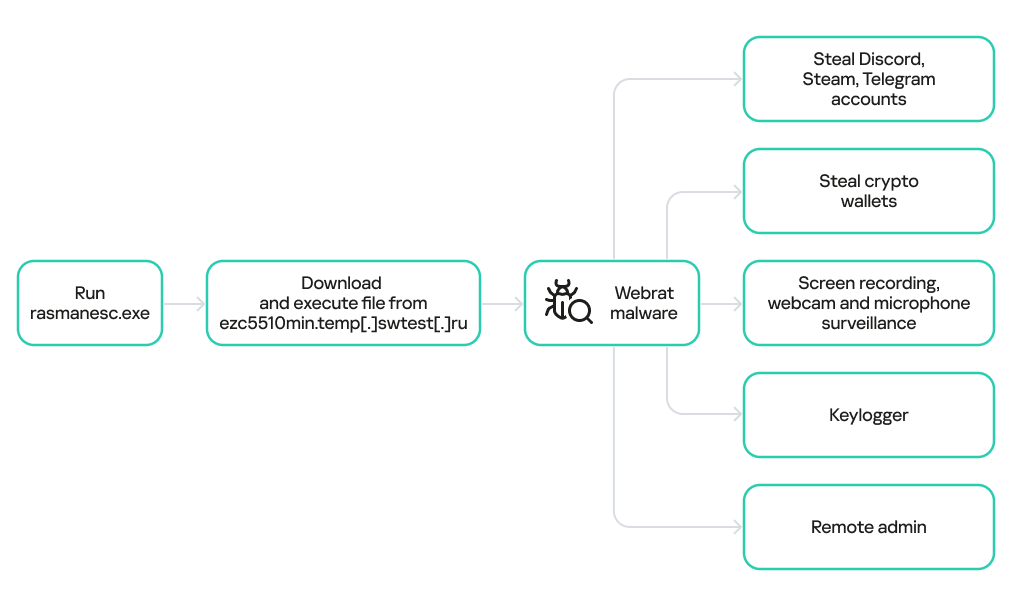

The infection chain itself is straightforward but effective. Users download what they think is an exploit repository. Inside is a password-protected ZIP archive containing several files. There's an empty decoy file to throw off basic analysis. There's a fake DLL. And most importantly, there's a batch file and a malicious executable called rasmanesc.exe. This dropper is where the real damage happens.

Once executed, rasmanesc.exe doesn't announce itself. It doesn't pop up warning windows. Instead, it quietly elevates its own privileges, disables Windows Defender, and then downloads the actual Web RAT backdoor malware from a remote command-and-control server. By the time a user realizes something's wrong, the attacker already has persistent access to their system.

GitHub has removed all identified malicious repositories. That's good news for future users. The bad news? Anyone who downloaded packages before removal is now walking around with a potentially active backdoor on their machine. And given that this campaign ran for several months before detection, the actual infection count is likely much higher than we'll ever know.

The broader lesson here cuts deeper than just "GitHub has malware." What we're seeing is threat actors getting smarter about where and how they distribute attacks. They're not just targeting home users anymore. They're targeting the infrastructure of security itself.

Understanding Web RAT: More Than Just a Backdoor

Web RAT isn't a household name like Emotet or Ransomware-as-a-Service operations, but it deserves attention precisely because of what it can do once installed on a system.

At its core, Web RAT is a remote access trojan (RAT) combined with an infostealer. The distinction matters. A standard RAT gives attackers control of a system from a distance. They can execute commands, manipulate files, and move laterally through a network. An infostealer focuses on extracting valuable data: credentials, browser history, cached passwords, sensitive documents, anything an attacker can convert into money or leverage.

Web RAT does both, which makes it dangerous in different ways depending on who's using it.

The remote access component means an attacker sitting in another country can essentially operate your machine like they're sitting at your keyboard. They can open applications, run scripts, install additional malware, or pivot to other systems on your network. If you're a security researcher with access to internal tools, corporate networks, or sensitive testing infrastructure, this is catastrophic. An attacker can move through your organization's systems while making it look like legitimate user activity.

The infostealer component is where personal damage happens. Web RAT harvests credentials from browsers, email clients, and credential managers. It can extract SSH keys, API tokens, and authentication certificates. For someone working in cybersecurity with elevated permissions and access to multiple systems, compromised credentials become a master key that opens doors across an entire security infrastructure.

What separates Web RAT from older RATs is its modular design. The initial dropper is relatively simple—elevate privileges, disable antivirus, download the real payload. But once installed, the actual Web RAT malware can receive updates and additional modules from the command-and-control server. An attacker could start with basic reconnaissance, then add cryptomining modules, ransomware capabilities, or lateral movement tools. The victim's machine becomes whatever the attacker needs it to be.

The infection vector through fake PoC exploits is particularly clever because it exploits the psychology of security researchers. When a critical vulnerability gets disclosed, security professionals want to understand it. They want to test it in controlled environments. They want the exploit code. Providing what looks like that code—bundled in a legitimate-looking GitHub repository with documentation that reads naturally—hits directly at their professional incentives.

It's not a vulnerability in GitHub's platform per se. GitHub's security team did what they could once alerted. The vulnerability is in the trust layer. The expectation that content within professional repositories is vetted or at least reasonably legitimate. When someone claims to have exploit code for CVE-2025-XXXXX and provides what looks like working documentation, most security professionals won't submit it for deep forensic analysis before testing. They'll test it in a sandbox first—and that's when the dropper executes and starts its real work.

The AI-generated documentation adds another layer of plausibility. Generative AI has gotten good enough that it can write functional documentation that sounds like it was written by a real security researcher. Syntax is correct. Terminology is appropriate. The explanation of the vulnerability and why the exploit works sounds knowledgeable. You can't tell from reading it that an AI generated the content.

Once Web RAT is installed, the attacker has multiple options. They could immediately exfiltrate credentials and move on. They could maintain persistent access and monitor the system for sensitive activity over weeks. They could use it as a jumping-off point to attack other systems on the network. For organizations with security researchers or developers using compromised machines, the potential damage spans data theft, intellectual property loss, and supply chain compromise.

The fact that the campaign started in September 2025 and ran for several months before discovery suggests the actual success rate was higher than we might expect. GitHub repositories get less scrutiny than other distribution vectors. Antivirus software often trusts code from GitHub repositories more readily. And security researchers, by profession, are more likely to examine code before running it—but they're also the most likely to think "I know what I'm doing, I'll test this in a sandbox first."

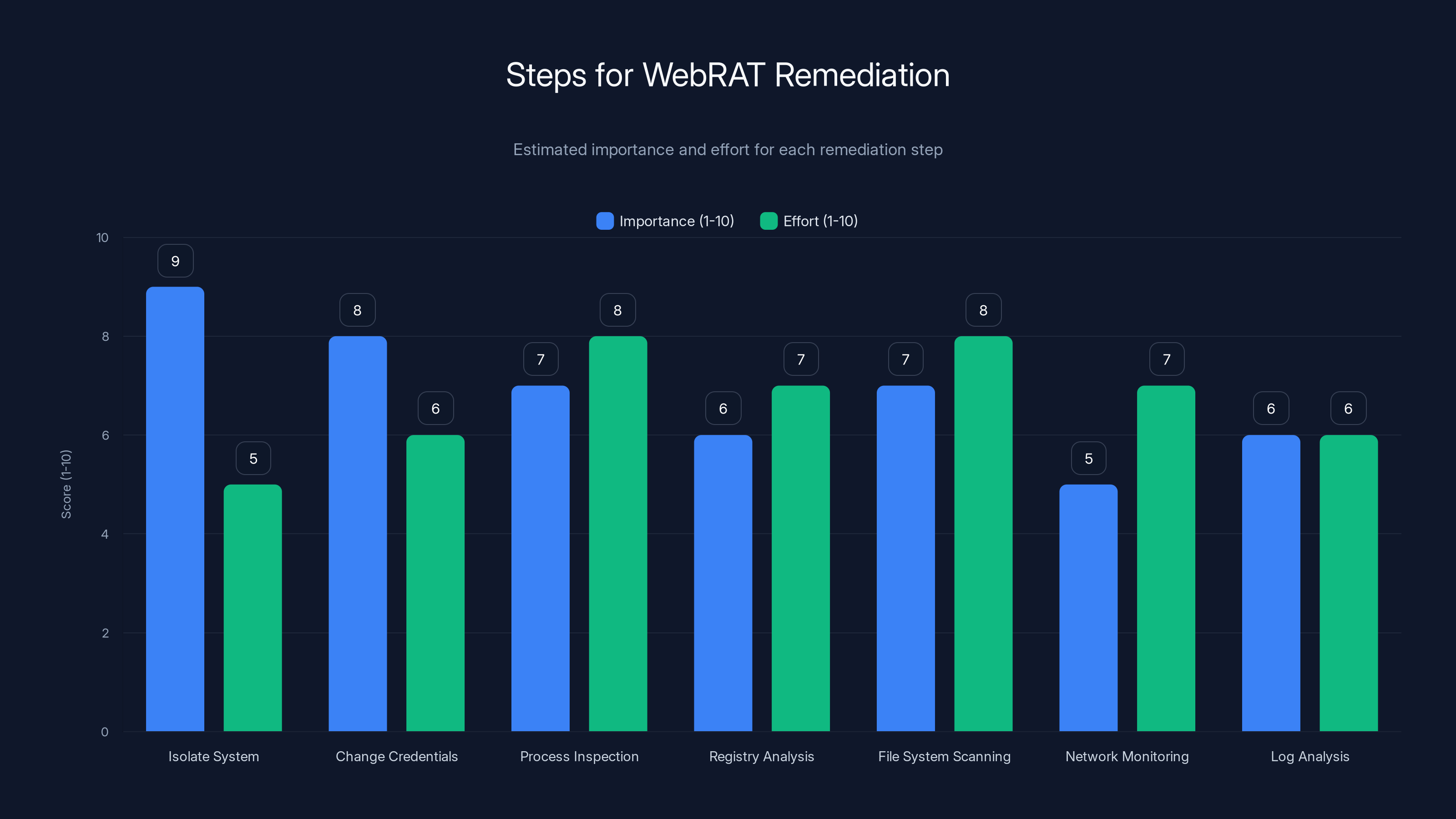

Isolating the system and changing credentials are crucial first steps with high importance. Process inspection and file system scanning require significant effort.

The Attack Chain: How Dropper Becomes Backdoor

Let's walk through what actually happens when someone downloads and executes the malicious package. Understanding the attack chain helps explain why this campaign was effective and what needs to happen to clean an infected system.

Stage 1: The Download and Extract

The user downloads a ZIP file from the GitHub repository. The filename might be something like "cve-2025-0001-exploit.zip" or "poc-vulnerability-proof.zip." Nothing immediately suspicious. Inside the archive is a password-protected layer—the password was likely provided in the repository's README file, which adds another layer of legitimacy.

When extracted, users see multiple files: one or two empty decoy files, a fake DLL with a name that suggests it's part of a legitimate Windows library, the batch script, and rasmanesc.exe. At this point, someone browsing the directory might see what looks like a normal Windows utility or exploit tool.

Stage 2: Execution and Privilege Escalation

The user runs rasmanesc.exe, thinking they're executing an exploit tool. This is where the malware begins its work.

Rasmanesc immediately attempts to elevate its privileges. It does this through multiple techniques that vary depending on what's available on the system. On older Windows installations, it might exploit known privilege escalation vulnerabilities. On newer systems with User Account Control (UAC) enabled, it might attempt to bypass UAC through legitimate Windows mechanisms or known exploits. The goal is simple: get from user-level permissions to system-level permissions.

Once elevated, the dropper takes its next crucial step: disabling Windows Defender. This isn't subtle. It modifies Windows registry keys that control security software, potentially adding itself to exclusion lists or simply terminating the antivirus process. On systems with third-party antivirus, it might attempt to kill those processes too or disable their network components.

This is the point where a user might notice something is wrong if they're watching their system closely. Windows Defender alerts disappear. Security notifications stop showing up. But most users aren't watching their system at the process level. They've executed what they thought was legitimate software. They're not expecting malicious activity. The dropper appears to complete its work and might even display a fake success message or legitimate-looking error that makes the whole thing seem normal.

Stage 3: The Download and Installation of Web RAT

Now elevated and with antivirus disabled, rasmanesc.exe reaches out to a remote command-and-control server and downloads the actual Web RAT malware. This download happens over the network, but without antivirus monitoring and network traffic inspection, nothing stops it.

Web RAT gets installed into a system directory, likely with a name that sounds like a legitimate Windows service. The attacker might register it as an actual Windows service, ensuring it starts automatically every time the computer boots. Or they might install it into the user's App Data directory and establish persistence through Registry run keys or startup folders.

At this point, the dropper's job is complete. Rasmanesc.exe might delete itself to cover its tracks, or it might simply sit dormant. The machine now hosts an active Web RAT instance with persistent access.

Stage 4: Command and Control Communication

Once installed, Web RAT begins communicating with the attacker's command-and-control infrastructure. These communications might be encrypted to avoid detection by network monitoring tools. They might use legitimate-looking protocols like HTTPS to blend in with normal traffic.

The attacker now has remote access. They can execute commands on the system, retrieve information about the infected machine, exfiltrate files, install additional malware, or simply monitor the system for interesting activity. If the infected user has credentials stored in their browser or credential manager, Web RAT extracts them. If they access sensitive systems or files, Web RAT can capture that activity.

For a security researcher or developer, this is particularly dangerous. They likely have access to internal systems, proprietary code, security testing infrastructure, or confidential documentation. An attacker maintaining access through Web RAT could essentially shadow a user's activity indefinitely, stealing everything of value.

Detection and Why It's Hard

Detecting Web RAT after it's installed is harder than it should be. The malware runs in system context, making it harder for user-level antivirus to detect. Communications might be encrypted. Behavioral patterns might mimic legitimate applications. An infected user might see nothing unusual on their system.

The reason this particular campaign lasted months before discovery wasn't because Web RAT is undetectable. It's because the delivery vector was trusted. Users didn't suspect the GitHub repositories. Kaspersky eventually found them through threat intelligence operations, not through detecting the malware on infected systems.

Once a user realizes they're infected, manual remediation is necessary. Simply removing the files might not be sufficient because the attacker might have installed additional persistence mechanisms. Complete system reinstallation is often the only way to be truly certain Web RAT is gone.

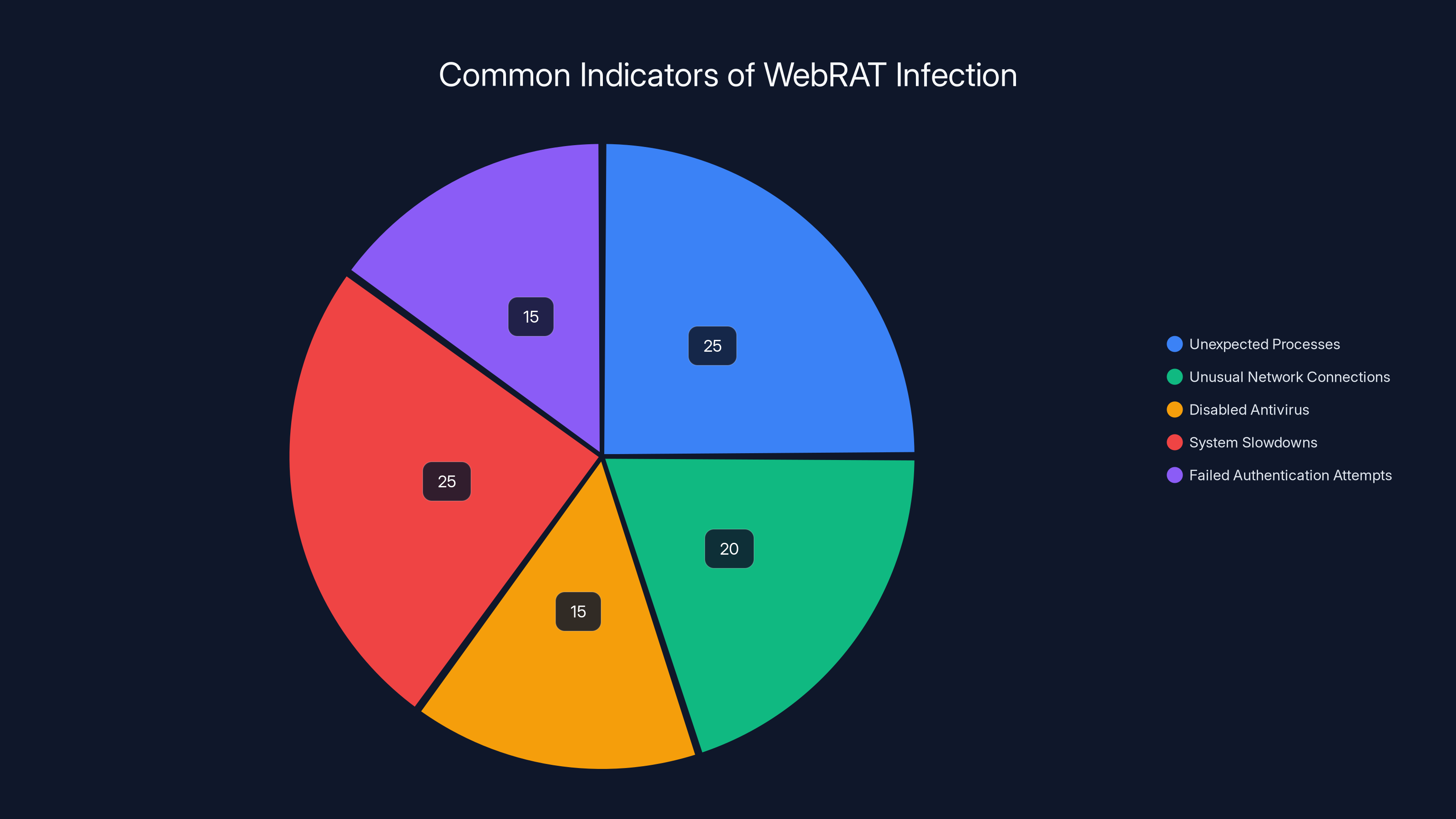

Estimated data shows that unexpected processes and system slowdowns are the most common indicators of WebRAT infection, each accounting for 25% of cases.

Why GitHub? The Platform as Trojan Horse

At first glance, using GitHub to distribute malware seems counterintuitive. GitHub is owned by Microsoft, one of the world's largest technology companies with significant security resources. The platform has abuse detection systems, takedown teams, and security researchers constantly looking for malicious content. Why would sophisticated threat actors choose such a visible, monitored platform?

The answer reveals something important about how security works in practice versus how we imagine it works.

Trust as the Fundamental Vulnerability

GitHub occupies a unique position in the software development ecosystem. It's not just a code repository. It's a social network for developers. It's a resume. It's where innovation happens. For security researchers specifically, GitHub is where tools are shared, exploits are published, and the latest security research lives.

When someone sees a GitHub repository, their threat model assumes certain baseline protections. GitHub has abuse teams who remove malicious content. GitHub's Terms of Service explicitly prohibit malware distribution. GitHub verifies its users. If content made it to GitHub, surely some baseline vetting happened.

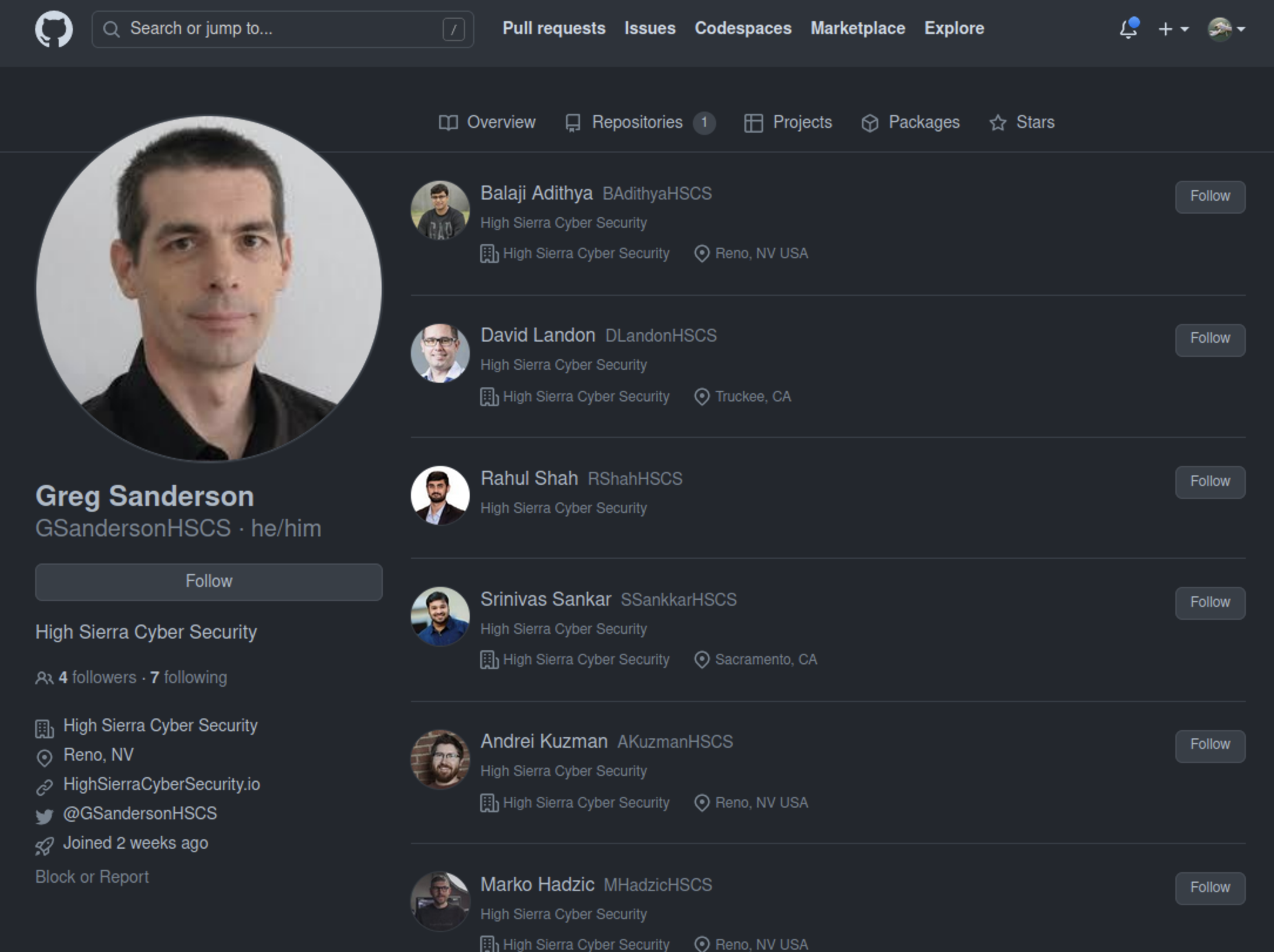

None of those assumptions were actually violated by the Web RAT repositories. The content genuinely looked like exploit code. The repositories genuinely had documentation. The profiles that created them genuinely looked like security researchers. GitHub's automated systems didn't flag them because the payload was separated from the distribution mechanism—the malware wasn't in the visible repository files, it was in an external download triggered by a dropper.

This creates a detection gap. GitHub's security scanners can look for obvious malware in code files. They can look for links to known malicious domains. But when a repository contains what looks like legitimate security research, and the actual malware is downloaded only after execution, detection becomes harder.

Scale and Targeting Precision

GitHub's user base skews heavily toward developers and security professionals. These are valuable targets. A cybercriminal who infects a random user's computer might get their banking credentials and some personal files. A cybercriminal who infects a security researcher's computer gets access to internal security testing tools, vulnerability databases, information about unreleased security research, and potentially credentials that provide access to enterprise systems.

GitHub essentially provided attackers a way to precisely target their desired victim population. The security community congregates there. When a new vulnerability is disclosed, they congregate even more tightly, looking for exploit code. The attacker simply needed to create repositories that appeared at the right moment, with the right naming, in the right language, discussing the right vulnerabilities.

This is micro-targeting with massive scale. Traditional malware distribution through email or compromised websites has lower conversion rates because they're untargeted—most recipients aren't interested in the lure. GitHub-based distribution could have much higher success rates because it targets people actively looking for the exact content being offered.

The Network Effect and Social Proof

GitHub repositories gain credibility through network indicators. Stars, forks, pull requests, and contributing users all signal legitimacy. Early in the campaign, attackers might have seeded their repositories with these signals—getting other accounts to star the repositories, creating pull requests that look legitimate, building out contributor networks.

The presence of multiple versions of the "same exploit" across different repositories adds credibility too. If ten different repositories claim to have PoC code for a vulnerability, and nine are legitimate and one is malicious, the malicious one benefits from the legitimacy of the others. Users might assume all ten must be legitimate.

This is the network effect weaponized against security communities.

The AI-Generated Documentation Advantage

Previously, creating convincing fake repositories required someone to write legitimate-sounding documentation. That's a bottleneck. Documentation is hard to write. It requires understanding the vulnerability, understanding how exploits work, and being able to explain both clearly.

Generative AI removes that bottleneck. An attacker can feed an AI system: "Write documentation for a proof-of-concept exploit for CVE-2025-XXXXX. The vulnerability is X. The exploit works by Y. Include installation instructions and usage examples." The AI generates documentation that sounds like it was written by someone who understands the topic.

This democratizes malware repository creation. You don't need someone with deep security expertise. You need someone who understands how to use AI and how to structure a malware delivery chain. The AI handles the hard part of making it sound legitimate.

Why Traditional Distribution Failed

Malware distribution has gotten harder over the past decade. Traditional vectors—email attachments, compromised websites, software cracks—are increasingly defended against. Email security systems scan attachments. Browsers warn about malicious sites. Users have learned not to download sketchy software.

But security researchers still download code from GitHub. That's their job. They analyze threats. They test exploits. They need the actual code to understand vulnerabilities. GitHub distribution specifically targets people whose professional role includes executing unknown code in controlled environments.

It's not a vulnerability in security awareness. It's a fundamental conflict: security researchers need to analyze threats, which means executing suspicious code. The Web RAT campaign exploited this necessity.

The Infection Impact: What Happens After Compromise

Comprehending the real damage Web RAT causes requires understanding the different impacts based on who gets infected.

For Individual Security Researchers

An independent security researcher who downloads malicious PoC code is now compromised. Web RAT runs silently on their machine. Their SSH keys, stored credentials, and authentication tokens get exfiltrated. If they have a personal server where they host security research, the attacker now has credentials to access it. If they have accounts on multiple security platforms or participate in bug bounty programs, those credentials are stolen.

The attacker can then impersonate this researcher. They could post malicious code under the researcher's account. They could compromise bug bounty submissions. They could use the researcher's reputation to distribute additional malware more effectively.

Over time, the infected researcher might share credentials verbally or through messages with colleagues. They might access internal company systems from their personal computer. Each of these activities potentially spreads the compromise wider.

For Corporate Security Teams

When a security team member brings Web RAT into a corporate environment, the impact scales dramatically. Corporate security teams have elevated access. They often have administrative credentials for testing infrastructure. They might have access to vulnerability databases, security tools, or information about internal systems before exploits exist.

An attacker with access to a security team's machines can steal that information and sell it to other threat actors. They can use it to attack the organization itself. They can monitor when new vulnerabilities are discovered internally and develop exploits before public disclosure.

Moreover, security teams often have segregated networks and elevated access for testing. Web RAT running on a security researcher's machine could potentially be used to breach those segregated networks, gaining access to security infrastructure that's normally isolated from regular corporate networks.

For DevSecOps and Development Teams

Developers who download malicious PoC code are less likely to be directly targeted for their credentials (though those still matter). Instead, attackers focus on what developers have: access to source code repositories, development environments, and deployment pipelines.

An infected developer's machine could be used to inject backdoors into legitimate software being developed. The Web RAT malware could monitor the development environment and steal intellectual property. It could exfiltrate API keys and deployment credentials, giving attackers the ability to push malicious code into production systems.

When developers are compromised, the damage extends beyond that individual to every system and user that depends on the software they build.

The Long Tail of Compromise

What makes this particularly dangerous is that Web RAT infections aren't immediately obvious. An infected researcher might not notice their system has been compromised for weeks or months. During that time, the attacker is continuously stealing information and maintaining access.

Compromise discovery often happens by accident. A system is slow and you check running processes. A credential gets rejected in an odd way and you wonder why. Someone mentions they got access denied trying to use your credentials. By the time compromise is discovered, extensive damage has already occurred.

For anyone infected before the malicious repositories were removed, the question isn't whether they were compromised—it's whether they've been compromised and for how long. Even researchers who deleted the files after infection should assume their system is compromised. The dropper accomplished its mission: Web RAT was installed and likely established persistence that survives file deletion.

Kaspersky identified 15% of analyzed GitHub repositories as malicious, highlighting a significant threat within trusted platforms. Estimated data based on narrative.

Detection Challenges: Why This Campaign Succeeded

Kaspersky's discovery of this campaign is interesting precisely because it wasn't discovered through traditional malware detection. Antivirus software didn't catch it en masse. Endpoint detection and response systems didn't raise widespread alerts. Instead, Kaspersky found it through threat intelligence operations—essentially, someone was paying attention to security research distribution channels and noticed patterns.

This points to fundamental detection gaps that the campaign exploited.

Signature-Based Detection Limitations

Traditional antivirus works by maintaining signatures of known malware. When files are scanned, their signatures are compared against a database. If there's a match, the file is quarantined.

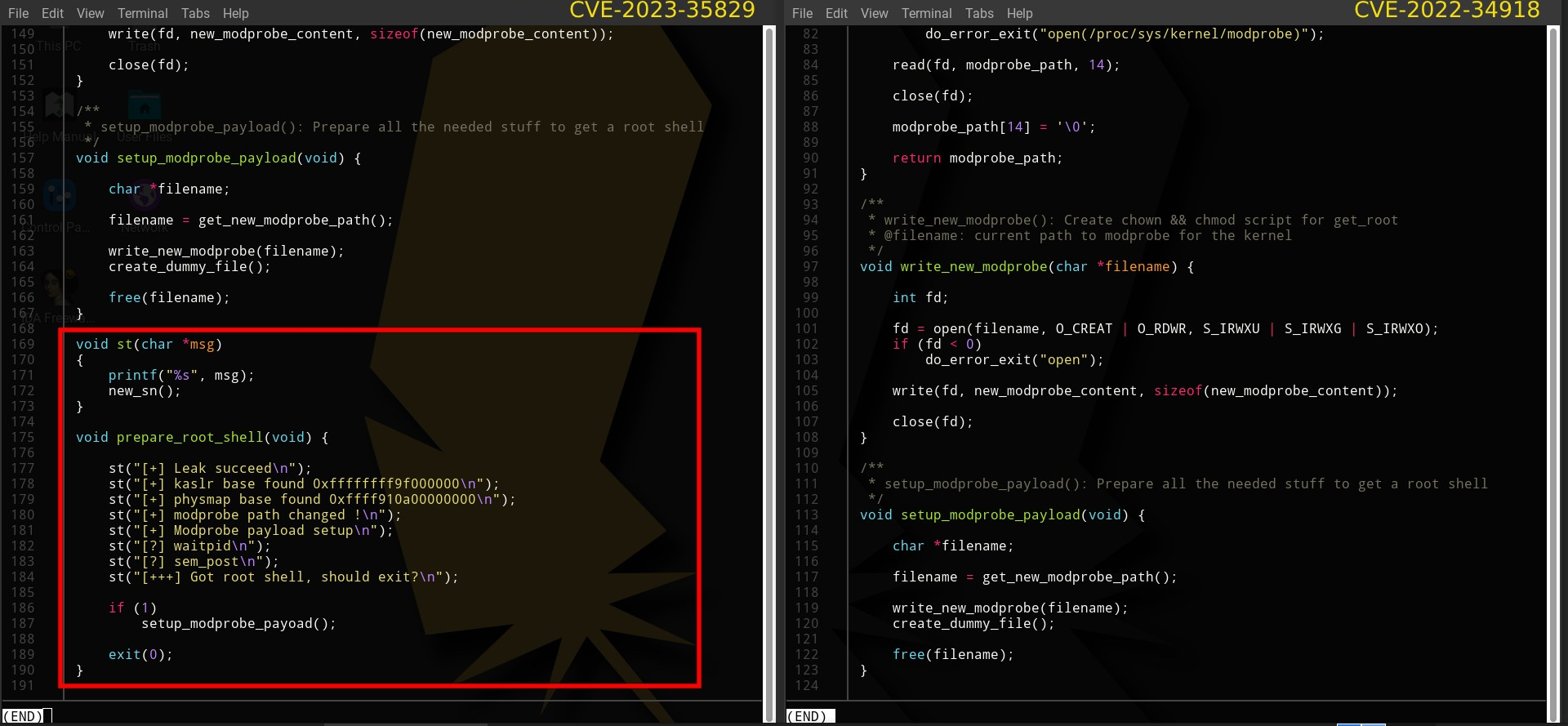

The Web RAT campaign exploited this through separation of concerns. The actual Web RAT malware wasn't present in the GitHub repository. The dropper (rasmanesc.exe) was, but that's a single component with limited functionality. If antivirus detected rasmanesc.exe as malicious, it would only prevent that specific file from executing—and attackers can recompile it with different signatures.

The malware was downloaded after execution, only after the dropper established proper conditions (privilege elevation, antivirus disabled). By the time Web RAT was downloaded, antivirus was already disabled. Signature-based detection never had a chance to see it.

Behavioral Detection Issues

Modern antivirus attempts behavioral detection. Instead of looking for known malware, it looks for suspicious behavior: privilege escalation, antivirus disabling, unauthorized network connections, registry modifications.

Web RAT's behavior patterns, once installed, are somewhat generic. Remote access tools need network connections, but those connections might mimic legitimate applications. Data exfiltration could look like legitimate file transfers. Credential theft involves accessing Windows credential stores, but legitimate applications do this too.

The real behavioral red flag—the privilege escalation and antivirus disabling—happens in the dropper, not in Web RAT itself. If antivirus is disabled before Web RAT is installed, behavioral detection of Web RAT becomes much harder.

Network Detection Challenges

Ideally, command-and-control communications between Web RAT and the attacker's server would be detected by network security tools. But if communications are encrypted and use standard protocols like HTTPS, they're invisible to standard network inspection.

Moreover, a compromised system connected to the internet can reach out to anywhere. Unless an organization has extremely tight network controls, blocking outbound connections to unknown external IP addresses, the malware can communicate freely.

The GitHub Reputation Factor

Security tools often have exemptions for trusted sources. GitHub might be whitelisted in corporate environments. Code downloaded from GitHub might be excluded from deep scanning. Processes running from GitHub-downloaded files might be trusted by default.

The Web RAT campaign exploited this reputation. Malware distributed through GitHub had an inherent credibility advantage over malware distributed through unknown sources.

Human Factor and Trust

Beyond technical detection, the campaign exploited human trust. Security researchers are trained to analyze threats, but they're also incentivized to move quickly. A new vulnerability? They want the exploit code now. Waiting for reputation verification, deep analysis, or source validation delays their work.

When time pressure and professional incentive align with what appears to be legitimate content, human detection rates drop. Researchers who might normally be suspicious of unknown sources trust GitHub repositories. They might still use sandboxes for analysis, but a sandbox execution is still execution—and that's enough for the dropper to work.

The Months-Long Gap Before Detection

The campaign started in September 2025 and ran for several months before Kaspersky detected and reported it. That timeline suggests traditional detection mechanisms failed almost entirely. If antivirus had caught the dropper, if behavioral detection had flagged the privilege escalation, if network detection had caught the CNC communications, the campaign would have been disrupted much sooner.

The gap exists because the campaign was designed to defeat each layer of defense. It wasn't sophisticated in the way advanced persistent threats are sophisticated. Instead, it was designed to be just sophisticated enough to bypass the specific defenses that guard against distribution channels like GitHub.

Remediation: Getting Web RAT Off Your System

If you downloaded packages from the malicious repositories before they were removed, you need to assume your system might be compromised. Remediation isn't a simple process.

Immediate Steps

First, isolate the affected system. Disconnect it from the network. Don't use it to access anything sensitive. Don't assume that simply deleting files or running antivirus will fully remove Web RAT. The malware has likely established persistence mechanisms that survive simple file deletion.

Second, change credentials from a different, uncompromised system. Any password, SSH key, API token, or authentication credential that could have been stolen needs to be regenerated. If you have accounts on multiple systems, all of them should have passwords changed.

Third, assume all cached credentials are compromised. This includes browser credentials, SSH keys, API tokens, and anything stored in credential managers. Regenerate or rotate everything.

Deep Cleaning Approaches

Manual remediation is possible but tedious. Web RAT might be installed as a Windows service, a scheduled task, a registry run key, or in startup folders. It might have multiple files, DLLs, and supporting infrastructure. Finding and removing all of it requires:

-

Process inspection - Look for suspicious running processes. Web RAT might disguise itself with a Windows-like name, but unusual network connections or unexpected system directory files are red flags.

-

Registry analysis - Check for new services, run keys, scheduled tasks, and shell extensions that might indicate persistence mechanisms.

-

File system scanning - Search for newly created files in system directories, App Data, and temporary folders. Pay attention to modification timestamps around when the dropper was executed.

-

Network connection monitoring - Look for unexpected outbound connections to external IP addresses.

-

Log analysis - Check Windows event logs for signs of privilege elevation, antivirus disabling, or suspicious process creation.

This is feasible for experienced security professionals, but it's also easy to miss persistence mechanisms. Attackers are often more thorough about covering their tracks than individuals are about finding them.

Complete Reinstallation

The safest remediation is complete system reinstallation. Backup only essential files (not executables or system files), then:

- Boot from installation media

- Perform a clean install of the operating system

- Update the OS and all software

- Restore non-executable files from backup

- Change all credentials again from the clean system

- Monitor the system closely for several weeks

Reinstallation takes time, but it guarantees the malware is gone. You can't accidentally miss a persistence mechanism if you've wiped the entire system.

Post-Remediation Vigilance

After removing Web RAT, the work isn't finished. Monitor systems closely for several weeks. Look for unexpected processes, network connections, or behavior changes. If the system was compromised for an extended period, the attacker might have installed additional backdoors or persistence mechanisms beyond Web RAT itself.

Most importantly, understand what information was potentially accessed during the infection window. If you stored sensitive data, accessed private systems, or used credentials from that computer, those assets should be audited for unauthorized access.

Estimated effectiveness scores suggest that implementing code sandboxing and zero trust architecture are among the most effective strategies for mitigating security risks.

Broader Security Implications: Threats to the Security Community

The Web RAT campaign represents a troubling trend: targeting the security community itself. Security researchers, developers, and system administrators are increasingly attractive targets because their compromises have amplified impact.

Supply Chain Risk Through Researchers

When a security researcher is compromised, the entire supply chain they touch becomes vulnerable. If they publish security research, their research platform could be used to distribute malware. If they contribute to open-source projects, those projects could be compromised. If they consult for organizations, those organizations' systems become targets.

The security community's strength comes from sharing knowledge and collaborating on defenses. A compromised researcher becomes a vector for spreading compromise throughout that network.

Erosion of Trust in Legitimate Resources

This campaign damages trust in GitHub and exploit distribution channels generally. Future researchers will be more cautious about downloading code from repositories, even legitimate ones. This slows security research and makes vulnerability analysis harder.

Ironically, defensive security improves when researchers can freely analyze threats. By damaging trust in repositories, this campaign actually makes the security community less effective at defending against threats generally.

The AI-Enabled Threat Evolution

The use of generative AI to create convincing documentation signals a new phase in malware distribution. When creating fake resources required specialized knowledge, it limited who could conduct these campaigns. When AI handles the knowledge-heavy parts, attack barrier drops significantly.

We should expect more campaigns using AI-generated documentation, websites, communications, and even code. Detection becomes harder because the output of AI is indistinguishable from human work. Attribution becomes harder because the AI-generated content provides no obvious signatures of authorship.

Targeting of Elevated-Access Individuals

Security researchers, developers, and system administrators have the most valuable compromises. Their access is broader. Their credentials are more powerful. Their machines are trusted by more systems. Yet these are also the groups most likely to download and execute unknown code as part of their work.

This creates an impossible position: do your job well, you become a target. Refuse to analyze potential threats, you can't do your job. The only solution is better detection and faster incident response when compromise happens.

Defensive Strategies: Hardening Against Similar Threats

Organizations and individuals can't prevent all threats, but specific defensive measures reduce the effectiveness of campaigns like this.

Sandboxed Execution Environments

When analyzing unknown code, use sandboxed environments. Virtual machines, containers, or dedicated sandboxing solutions isolate malware from the rest of your system. Malware running in a sandbox can't access credentials from your main system or establish persistence that survives the sandbox closure.

For developers and security researchers who regularly execute unknown code, sandboxing should be mandatory. The performance hit is worth the security gain.

Credential Isolation and Segmentation

Don't reuse credentials across systems. If your GitHub credentials are the same as your work system credentials, a compromise of your personal GitHub account spreads the damage. If your SSH keys for testing are the same as your SSH keys for production, a compromise of your test environment reaches production.

Use separate credential sets for separate risk domains. Use hardware security keys where possible. Implement multi-factor authentication on all sensitive accounts.

Network Segmentation and Monitoring

Isolate machines that analyze unknown code from systems that access sensitive data or credentials. Monitor network traffic from high-risk machines. Alert on unexpected outbound connections to external addresses.

Network segmentation doesn't prevent malware execution, but it prevents compromise from spreading beyond the initially infected system.

Behavioral Monitoring and Response

Implement tools that monitor system behavior for suspicious activities: privilege escalation, antivirus disabling, unusual process creation, credential access. These tools alert security teams in near-real-time when suspicious behavior is detected.

Behavioral monitoring can't catch every threat, but it reduces the window between infection and detection from months to minutes.

Source Verification and Trust Evaluation

Before downloading code from GitHub repositories, verify the source:

- Check the repository's age and history. New repositories with only a few commits should be viewed with suspicion.

- Look at the repository's stars, forks, and contributor count. Popular repositories are less likely to be malicious (though not impossible).

- Check if the author has other legitimate projects and a history in the security community.

- Use multiple sources for the same exploit. If you can find the same PoC in multiple places from different authors, it's more trustworthy.

- Check security discussion boards and communities for mentions of the repository.

None of these are perfect. Attackers can fake repository history. But combining multiple signals gives better confidence.

Principle of Least Privilege

Run user accounts with minimal necessary permissions. If a researcher's day-to-day machine has administrative access, malware runs with administrative access. If it doesn't, some malware won't run and others will be more limited in what they can do.

A security researcher might need administrative access for their work, but they could have separate user accounts for different activities. The "analyzing unknown code" account might be less privileged than the "developing secure software" account.

Incident Response Planning

Assume compromise will happen. Have a plan for detecting it, isolating it, and remediating it. Know what systems you'll preserve for forensic analysis. Know which credentials you'll rotate first. Know how you'll determine the scope of the compromise.

Incident response plans dramatically reduce damage when compromises occur.

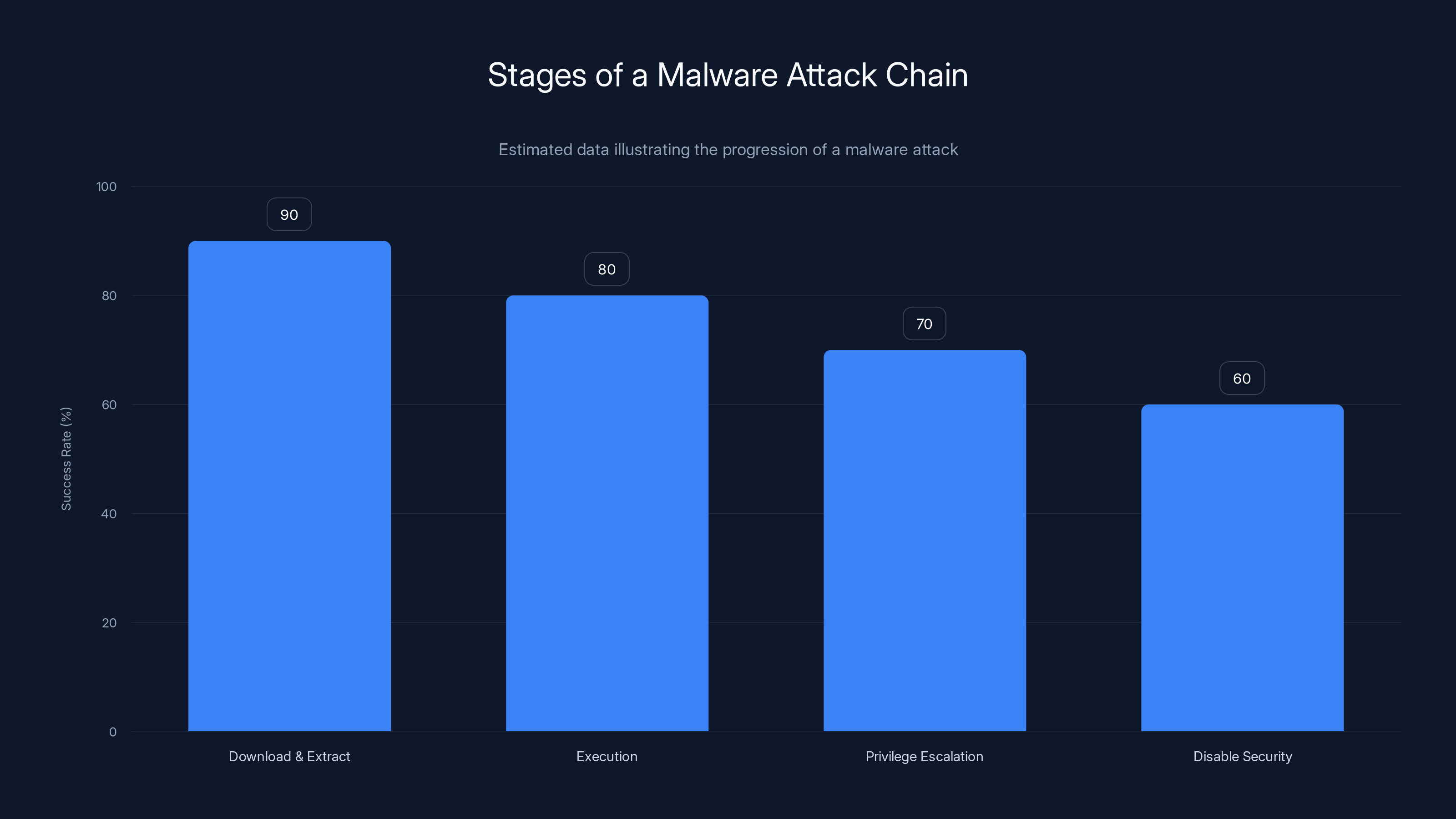

Estimated data shows that the success rate of each stage in a malware attack chain decreases as the attack progresses, with the highest success during the download and extract stage.

The Certification and Repository Verification Problem

One long-term solution to this problem is repository verification and certification. Right now, GitHub has no way to distinguish between verified, trustworthy repositories and unknown ones.

What Certification Could Look Like

A verification system might include:

- Author verification - Confirm the repository author's identity and security reputation through multiple channels.

- Code signing - Require that all malware or exploit PoC repositories be cryptographically signed by verified researchers.

- Peer review - Require that repositories claiming to contain exploit code undergo security review before publication.

- Timeline verification - Confirm that repositories claiming to contain PoC code for vulnerabilities are published only after the vulnerability is public.

These measures wouldn't stop all attacks—attackers would try to game any verification system—but they'd raise the bar significantly.

Practical Implementation Challenges

Implementing repository verification is harder than it sounds. GitHub would need to vet thousands of repositories. Verification delays publication, which slows security research. False positives (flagging legitimate repositories as suspicious) damage trust.

Moreover, certification systems create their own vulnerabilities. If a certification system is compromised or can be spoofed, the security community's trust in it becomes a liability rather than an asset.

Community-Driven Approaches

Alternatively, the security community could develop decentralized verification. Security researchers known in the community could review and recommend repositories. This is more scalable than centralized verification but relies on the community's ability to identify trustworthy reviewers.

Platforms like Hacker One, which connects security researchers with organizations, already do some of this work. Extending that to repository verification might be viable.

Looking Forward: Evolving Threats and Defenses

The Web RAT campaign demonstrates a new maturity in malware distribution targeting the security community specifically. What we'll likely see evolve in coming years:

AI-Enhanced Social Engineering

Generative AI will continue improving at creating convincing fake content. Repositories will look more legitimate. Documentation will sound more expert. Communications from fake researchers will be indistinguishable from real ones. This arms race between AI-enhanced attacks and AI-enhanced defenses will accelerate.

Targeting of Specific Platforms

Attackers will continue exploiting the specific properties of different platforms. GitHub is high-trust but also highly visible. Private repositories, internal code sharing systems, and specialized security research platforms might be targeted next. Each platform has different trust assumptions that attackers will exploit.

Supply Chain Attacks Through Researchers

We've already seen supply chain attacks through compromised open-source projects. Expect more sophisticated supply chain attacks that use compromised researchers as the initial foothold. If an attacker can compromise a well-respected security researcher, they can use that researcher's reputation to compromise organizations that trust them.

Specialized Malware for Analysts

Malware will become more sophisticated in targeting security researchers specifically. Instead of generic remote access, we might see malware that:

- Detects and reports to the attacker which security tools are analyzing it

- Behaves differently in sandboxed environments versus real systems

- Specifically exfiltrates analytical results and security testing data

- Impersonates the researcher to distribute compromise through their networks

Attackers have tremendous incentive to improve targeting of security professionals. We should expect them to do so.

Detection Evasion as a Core Feature

Malware families will compete on detection evasion capability. Web RAT's separation of dropper and payload was designed to evade detection. Future malware will incorporate additional evasion techniques:

- Polymorphic code that changes each execution

- Behavioral evasion that detects analytical tools and disables itself

- Encryption schemes that prevent signature detection

- Legitimate-looking network communications that evade behavioral detection

Counter-Intelligence Activities

Attackers will invest in counter-intelligence. Instead of just stealing information, they'll focus on not being detected. This includes:

- Misdirecting investigators toward false leads

- Mimicking legitimate system activity to avoid behavioral flagging

- Using the researcher's own tools against defensive measures

- Creating false evidence of compromise in different places to misdirect response efforts

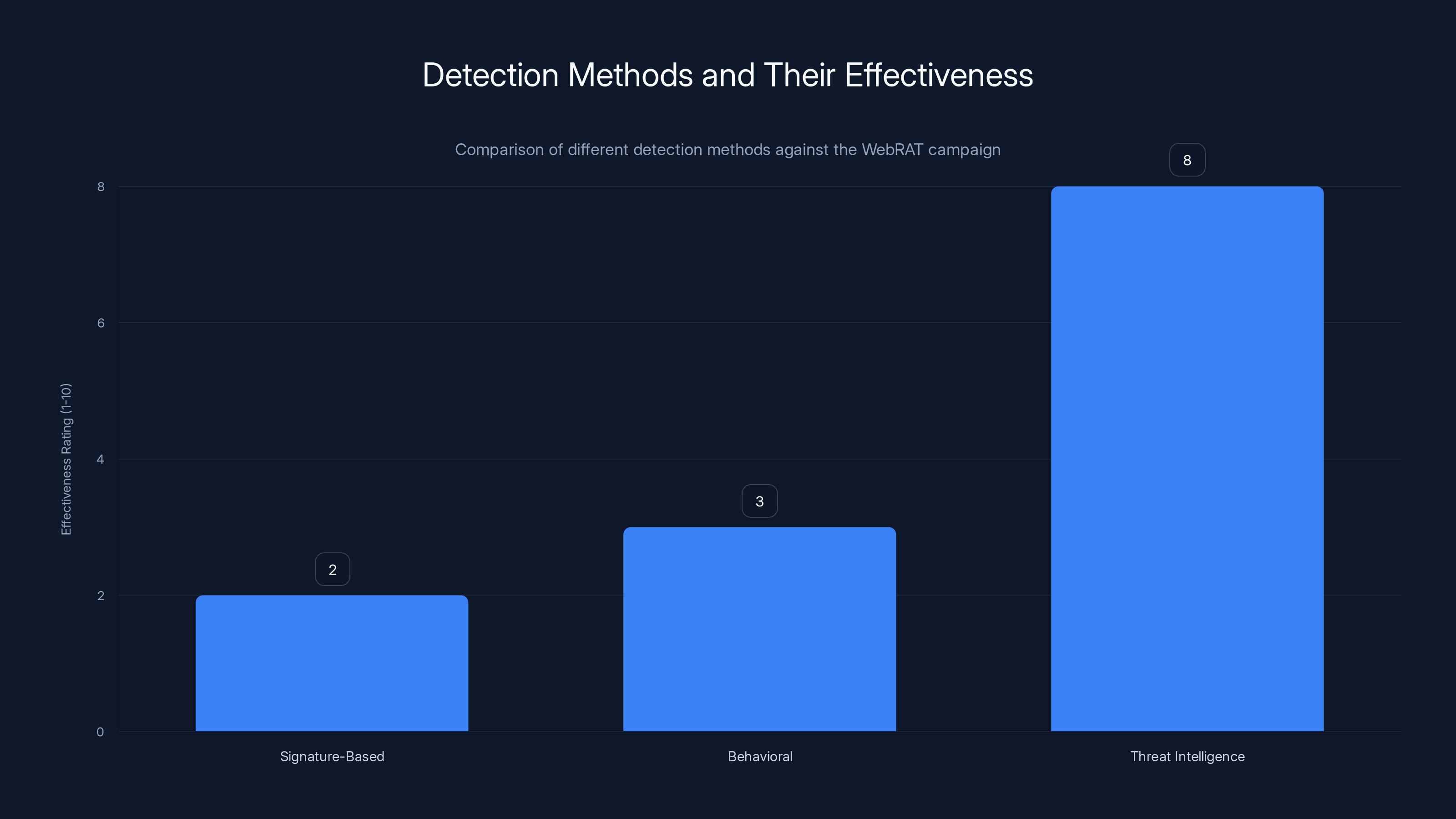

Threat intelligence was significantly more effective in detecting the WebRAT campaign compared to traditional signature-based and behavioral detection methods. Estimated data.

Organizational Response: What CTOs and Security Leaders Should Do

Security leaders and CTOs need to account for this threat in their security strategies.

Inventory High-Risk Activities

Identify team members who regularly download and execute unknown code. These are your highest-risk individuals. Prioritize protecting their systems and monitoring their activity.

Implement Code Sandboxing Mandates

Make sandboxed execution of unknown code mandatory, not optional. Provide the tools and infrastructure to make this practical. The performance cost is worth the security gain.

Segment Networks by Risk

Isolate machines that analyze threats from systems that access sensitive data or production environments. Make exfiltration harder even if malware successfully infects a research machine.

Deploy Behavioral Monitoring

Implement endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools that alert on suspicious behavior: privilege escalation, credential access, unusual process creation. Alert and respond in near-real-time to reduce the window between infection and containment.

Audit Credential Usage

Regularly audit which credentials have been used from which systems and at what times. If a researcher's credentials were used to access production systems from an unexpected location or time, that's a sign of compromise.

Implement Zero Trust Architecture

Assuming breach is inevitable, implement zero trust: verify every access request, authenticate continuously, monitor all activity. If malware infects a researcher's machine, zero trust architecture makes lateral movement and privilege escalation harder.

Create Incident Response Plans

Develop and regularly test incident response plans specifically for researcher compromise. Know who you'll call, what you'll isolate, what you'll preserve for forensics, and what your escalation path is.

Personal Security Measures: Protecting Yourself

For individuals working in security or development:

Separate Devices for High-Risk Activities

If you regularly download and analyze unknown code, consider using a dedicated device for that activity. This device should not have access to your primary credentials, email, or sensitive systems. If it gets compromised, the damage is isolated.

Use Virtual Machines

When testing unknown code, do it in virtual machines. Run VMs with network isolation when possible. Save clean snapshots before analysis, so you can revert to a known-good state if compromise occurs.

Credential Management Discipline

Use different passwords for every account. Use a password manager to track them. Use hardware security keys for sensitive accounts. When analyzing unknown code, don't have credentials for sensitive systems stored on that machine.

Network Monitoring

Monitor your home or office network for unexpected connections to external addresses. Look for devices communicating to unknown IP addresses. Set up alerts if your systems access unexpected network ranges.

Regular System Audits

Periodically audit your systems for signs of compromise:

- Check running processes for anything unfamiliar

- Review startup programs and scheduled tasks

- Look for new user accounts or privilege escalations

- Scan for unauthorized changes to system files

- Monitor your internet-connected devices for unusual activity

Assume Compromise and Act Accordingly

If you downloaded code from a repository that later proved malicious, assume your system is compromised. Change credentials from a clean system. Audit any systems you accessed from the potentially compromised system. Consider complete system reinstallation as the safest option.

Better to spend a day reinstalling your system than to spend months dealing with an active backdoor.

The Bigger Picture: Trust in an Age of AI-Generated Attacks

The Web RAT campaign highlights a fundamental tension in modern security: we need to trust systems and tools to be productive, but trust is increasingly weaponized against us.

Security researchers need to download and analyze exploit code. That's their job. But downloading from GitHub is now demonstrably dangerous. Yet completely avoiding GitHub would severely hamper security research. The middle ground—carefully vetting sources, using sandboxes, assuming compromise—is the realistic approach, but it's exhausting and error-prone.

Generative AI makes this worse. Before AI, creating convincing fake repositories required someone with genuine security knowledge. Now, any attacker can use AI to generate convincing documentation and explanations. Trust in content becomes harder because you can't assume the quality of writing indicates the legitimacy of the information.

This doesn't mean security research should stop. It means the security community needs better infrastructure for verification, better tools for safe analysis, and better incident response capabilities. It means organizations need to treat researcher compromise as a likely scenario and plan for it.

Most importantly, it means understanding that threats to the security community are threats to everyone. When researchers get compromised, defenses get weakened. When AI makes malware more convincing, everyone becomes more vulnerable. When trust in platforms erodes, the entire security landscape degrades.

The Web RAT campaign isn't just a problem for the 15+ people who downloaded malicious repositories. It's a signal that the threat landscape is evolving in ways that demand response at every level: technical, organizational, and personal.

Conclusion: What We Learned and What Comes Next

The discovery of Web RAT being distributed through malicious GitHub repositories wasn't a surprise to security professionals—it was a confirmation of fears that have been building for years. Threat actors had finally weaponized the trust and accessibility of developer platforms.

Here's what matters most: First, the threat is real and targeted. This wasn't mass malware distribution. It was precision targeting of security researchers and developers. Second, it worked. The campaign ran for months before detection, suggesting significant success rate in compromising targets. Third, the delivery mechanism exploited specific weaknesses in how security communities vet and distribute code.

Kaspersky's disclosure of the 15 malicious repositories, GitHub's removal of the content, and security teams' awareness of the threat represent the system working—but only after the threat had already compromised unknown numbers of victims. Detection happened through intelligence operations, not through automated security systems. That's a gap worth thinking about.

Going forward, three things need to happen: Organizations need to implement comprehensive detection and response capabilities specifically for researcher compromise. Security communities need better verification systems for code distribution, whether that's centralized certification or community-driven review. Individuals need to treat unknown code execution as the highest-risk activity and implement strict controls.

The malware itself—Web RAT—is less important than what it represents: sophisticated attackers have figured out how to target the security infrastructure itself. Defend against that, and the rest of security gets easier. Ignore it, and the entire defensive posture becomes vulnerable.

If you downloaded from any of the identified repositories, assume compromise and act accordingly. If you work in security, make sure your organization understands this threat and has plans to detect and respond to it. If you regularly analyze unknown code, make sure you're using sandboxes and keeping your credentials segregated.

The Web RAT campaign is over. The threat it represents is just beginning.

FAQ

What exactly is Web RAT and what can it do?

Web RAT is a remote access trojan (RAT) combined with an infostealer malware. Once installed, it gives attackers remote control of an infected system while simultaneously harvesting credentials, SSH keys, API tokens, and other sensitive data. The malware runs in system context, making it difficult for antivirus to detect, and can receive updates and additional modules from command-and-control servers, allowing attackers to expand its capabilities on demand.

How does the Web RAT distribution campaign work on GitHub?

Attackers created fake GitHub repositories that claimed to contain proof-of-concept exploits for real vulnerabilities. These repositories included AI-generated documentation that looked legitimate, along with a password-protected ZIP archive. Inside was a malicious dropper file named rasmanesc.exe that, when executed, elevates privileges, disables Windows Defender, and downloads the actual Web RAT malware from a remote server. The separation of the delivery mechanism (dropper) from the actual payload (Web RAT) made detection significantly harder.

How can I tell if my system is infected with Web RAT?

Detecting Web RAT after installation is difficult because it runs in system context and communicates over encrypted connections. Signs of possible compromise include unexpected processes running, unusual network connections to external IP addresses, disabled antivirus or security features, unexplained system slowdowns, or failed authentication attempts using credentials you know are correct. The most reliable detection method is using endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools that monitor system behavior, though the most certain way to confirm absence of infection is complete system reinstallation.

What should I do if I downloaded a file from one of the malicious GitHub repositories?

Immediately assume your system is potentially compromised. Isolate the affected machine from your network, change all credentials from a different clean system, and consider complete system reinstallation as the safest remediation option. If the system was used to access other systems or stored sensitive data, audit those systems for unauthorized activity. Do not reuse the affected machine for sensitive tasks until it has been completely cleaned, either through thorough manual remediation or reinstallation.

Why is GitHub being used for malware distribution when it's owned by Microsoft?

GitHub's position as a highly trusted platform in the developer community actually makes it attractive for malware distribution. Developers expect code from GitHub to be legitimate, and they're less likely to scrutinize repositories as thoroughly as they would code from unknown sources. Additionally, GitHub's automated security systems look for obvious malware signatures, but when malware is separated into a dropper and payload downloaded remotely, detection becomes much harder. The platform's reputation creates a trust advantage that attackers exploit.

Can antivirus software detect and remove Web RAT?

Antivirus software can sometimes detect the initial dropper (rasmanesc.exe) if it has a signature for it, but the actual Web RAT malware is designed to be harder to detect. Once Web RAT is installed, modern antivirus may have difficulty detecting it because it runs in system context and uses encrypted communications. The dropper specifically disables Windows Defender before downloading Web RAT, preventing detection at that critical moment. Complete system remediation often requires manual effort or full system reinstallation to ensure all persistence mechanisms are removed.

How does the use of AI in this campaign make it more dangerous?

Generative AI was used to create convincing documentation and explanations for the fake PoC repositories, making them appear legitimate to humans reviewing them. AI-generated content reads naturally and demonstrates apparent understanding of the vulnerability, eliminating a signal that security researchers might normally use to identify fake repositories. This lowers the barrier to entry for creating convincing malware distribution infrastructure, potentially enabling more threat actors to conduct similar campaigns without requiring deep security expertise.

What organizations or individuals are most at risk from Web RAT?

Security researchers, developers, security team members, and system administrators are highest risk because they regularly download and execute unknown code as part of their work. These individuals have elevated system access, valuable credentials, and connections to sensitive infrastructure. Compromise of a security professional impacts not just their individual systems but potentially extends to organizations they work with, security tools they manage, and research communities they participate in.

Should I stop downloading code from GitHub?

No, but you should implement strict protocols for code analysis and execution. Use dedicated virtual machines or sandboxed environments for testing unknown code. Verify repository sources and author reputation before downloading. Monitor the system closely after execution. Use separate credentials on analysis machines. Assume that any code from unknown sources might be malicious and isolate it accordingly. GitHub itself isn't the problem, the threat is in trusting unknown repositories without sufficient precaution.

What's the long-term solution to prevent similar campaigns?

Long-term solutions require multiple approaches: platforms like GitHub could implement repository verification systems or stronger author identity verification, the security community could develop decentralized trust networks for code recommendation, organizations should implement behavioral monitoring and sandboxing for code analysis, and individuals need to adopt zero-trust practices for downloading and executing unknown code. No single solution addresses the problem completely, but layered defenses—platform improvements, organizational policies, and individual practices—significantly raise the barrier to successful malware distribution through trusted platforms.

Key Takeaways

- Kaspersky discovered 15 malicious GitHub repositories spreading WebRAT malware disguised as proof-of-concept exploits with AI-generated documentation

- WebRAT is a remote access trojan and infostealer that establishes persistent backdoor access while harvesting credentials, SSH keys, and authentication tokens

- The attack chain uses a dropper (rasmanesc.exe) that elevates privileges, disables Windows Defender, then downloads WebRAT from remote servers

- Campaign successfully evaded detection for several months because malware was separated from distribution mechanism and GitHub's trust advantage was exploited

- Security researchers and developers face highest risk because their compromised machines provide attackers access to sensitive infrastructure and credentials

![WebRAT Malware on GitHub: The Hidden Threat in Fake PoC Exploits [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/webrat-malware-on-github-the-hidden-threat-in-fake-poc-explo/image-1-1766586518625.jpg)